Does being anti-war make you anti-liberation?

We can talk about the gore and horror of war without acquiescing to our oppressors.

A friend once joked that I’m bad at deescalating things on Twitter because I engage with anything stupid. That’s certainly true. For the last day or so I’ve been locked into a mindless debate where all sorts of charges have been levied against me—that I’m a liberal, that I use my Iranianness as a cudgel, that I support Israel, that I’m an apologist for American imperialism, and that, once more, I’m a liberal for doing so. This all started because I said—in the characteristically somber way that I say things these days—that the US and Israel are seeking to provoke Iran into a region-wide conflict, which would invariably result in the death and displacement of untold numbers. I expressed despair and dismay over this prospect, especially since my mother lives in Iran, and having lost one parent to US sanctions, I’m not keen to lose another one to US wars.

However, the internet did its thing and within a night these sentiments were somehow twisted as opposition to liberatory resistance and support for the continued slaughter of Palestinians. Essentially, an anti-war sentiment was repackaged as support for American militarism. So, instead of wasting another day on Twitter, I think it’s fitting to address a simple question: Does being anti-war equate to opposing the liberation of the oppressed?

The answer is an emphatic no. I’m not a pacifist, but even pacifism does not entail passivism. Likewise, being anti-war does not commit you to the requirement that you sit back and let the powerful terrorize the oppressed. To the contrary, being anti-war commits you to the requirement that you work to create conditions that would allow the oppressed to defend themselves—conditions that would ultimately render unnecessary the need for violent self-defense in the first place.

Furthermore, it is possible to acknowledge the gore and horror of war, even within the framework of liberatory violence, while still asserting that violence can be a justified means to advance the ideal of a just world. This is the position that I maintain—that uncivil and violent resistance are, in some contexts, critical elements of resisting one’s oppressor. At the same time, much like Edward Said, I also do not believe in what he once called “the purifying power of violence,” or the notion that violence will cleanse the earth of all evil. Acts of violence are often ugly, and ugliness tends to reproduce ugliness. Nevertheless, when all nonviolent means have been exhausted, violence may become the only recourse for the oppressed.

The internet is an ecosystem that fosters pointless disagreement, especially amongst people that otherwise might agree on many fundamental issues. Nonetheless, I was surprised by the reaction that my antiwar stance produced amongst certain segments of the so-called Online Left. Once more, being anti-war does not commit one to a blind opposition to all warfare, especially when force is employed in the service of breaking the oppressor’s rod. This is why I was taken aback by the excitement amongst certain Western observers who insist that war is a positive development—rather than a necessary one—in the pursuit of liberation. Violence of the oppressed is not an end in itself, but rather a utilitarian violence that seeks to lay bare the internal fragility of an order built upon the domination of one group by another. Its role has to be understood and appreciated within context, but it is not a spectator sport to be enjoyed; it is the type of violence that burdens the oppressed and materially and psychologically exacts a steep price.

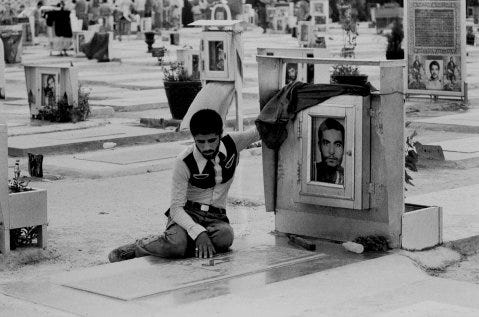

Those amongst us who have generationally endured the terrors of war are entirely justified in recoiling with horror at the prospect of more conflict, more death, more destruction. This does not negate, either practically or theoretically, the recognition that violence can serve a liberatory purpose. It also doesn’t undermine the understanding that such modes of violence arise in response to the violence inflicted by the powerful. Rather, this horror expresses something deeply human–the ability to appreciate the ugliness of war, grieve its victims, and bemoan a world that forces upon us a tradeoff between dramatic displays of violence and a flicker of hope for liberation.

I empathize with this. I have a lot of family there, many of which I have yet to meet in person due to conscription concerns.

I don't want regional war escalation, yet at the same time I wholeheartedly support liberation resistance measures. Tough situation to be in. You are not alone in that train of thought